Creativity broadly refers to a cluster of psychological processes and behaviors that enable individuals and groups to produce novel and useful contributions to their own lives and the lives of others. Inasmuch as creativity is associated with technological progress, artistic production, and entertainment, it is highly valued (Sawyer, 2012). Being instrumental, creativity can be used for evil ends. Much as deception, intrigue, and betrayal require social intelligence, so do they benefit from a creative mind (Gino & Wiltermuth, 2014; Mayer & Mussweiler, 2011). When regarded as a capacity or process, that is, independent of these potential outcomes, creativity (like money or knowledge) is value-free (Weber, 1917). People aregenerally quite interested in the nature and the process of creativity, and they ask how they might enhance their own creativity (or the creativity of their children, students, or employees). In this article, I review classic work on creativity and argue that each of these approaches captures some truth about the phenomenon, but that, taken by itself, each of these approaches is not just incomplete, but mistaken. Creativity, in my view, emerges from the dialectical interplay between opposing forces, where each force requires the existence of the other. Creativity would collapse if one of these forces were to win the struggle. It is the struggle that brings forth creativity. The article is organized as a series of seven dialectics. I introduce each dialectic with reference to the relevant classic sources. I conclude with an integrative summary and a note on the relationship between psychology of creativity and the psychology of judgment and decision-making.

Dialectic 1: Russell’s Paradox

Dual-process theories pervade (again) psychology. Aristotle, the Church Fathers, and Freud distinguished between a simple intuitive mind and a higher, more rational, mind (Dawes, 1976). Kahneman (2011) and other recent writers have reinforced this view. Decades ago, the noted humanist psychologist Abraham Maslow (1968) presented a dual-process argument with respect to creativity. He viewed creativity as a capacity characteristic of self-actualization, the highest human motive. Yet, in his view, creativity requires a partial regression to childlike spontaneity, playfulness, and disregard for public opinion. Spontaneity is a feature of a primary, unfettered, process, but this process cannot be completely unleashed. There needs to be a secondary process to maintain standards and conventions, a process that gives direction to the primary process and sets limits. What then is creativity? Is it the spontaneity of the primary process, or is it this spontaneity within the constraints imposed by the secondary process? Logically, it can’t be both, lest it be a case of Russell’s paradox. Critiquing classical set theory, Russell (1902) noted that a set cannot contain itself. A library catalogue cannot include itself in the list of books without being self-contradictory. Likewise, creativity cannot refer to both, a primary, intuitive process and the outcome of the interplay between the intuitive process and a policing, secondary process. However, a dialectic view of creativity is not troubled by such logical paradoxes. Instead of fearing refutation by contradiction, the dialectical perspective suggests that the phenomenon of interest emerges from the tension between opposing forces or ideas, it emerges as a synthesis from the interplay between thesis and antithesis.

Dialectic 2: Between Chance and Purpose

Where do spontaneous thoughts and behaviors come from? Most cognitive psychologists assume that mental events can be traced to external stimuli whose effects propagate through the mind’s web of associations. Not so Campbell (1960). Campbell proposed that ideas flow from an unconscious idea generator, which blindly churns out mutations of previous ideas. The analogy with genetic mutation and Darwinian evolution is deliberate. Given a copious supply of ever mutating ideas, occasionally one will fit a psychological task at hand. At that moment, it becomes conscious and yields an aha!-moment of insight. To Campbell, insight is the result of a process of blind variation and selective retention, and not an explanatory concept. Campbell’s proposal stands in dialectical contrast to the hypothesis that creative problem solving is a matter of systematic and effortful search, whereby a solution is approached and ultimately found by the careful stepwise elimination of options. This view was championed by the Gestalt psychologists (Wertheimer, 1959), and is well illustrated by Duncker’s (1945) analysis of the candlestick-matchbook problem. The dialectical view of creativity suggests that neither chance (Campbell) nor purpose (Duncker) can succeed on its own. Blind variation needs a criterion for success and purposeful search needs a mechanism to generate options. Guilford’s (1950) proposal that creativity engages an alternative intelligence captures this dialectic. Guilford distinguished between convergent thinking, which narrows options down until a single correct solution is found, and divergent thinking, which generates multiple diverse options (e.g., a list of ways in which a brick might be used). The primary process generates alternatives, but it does so within the constraints set by the criterion of usefulness.

Dialectic 3: Beyond Convention and Expertise

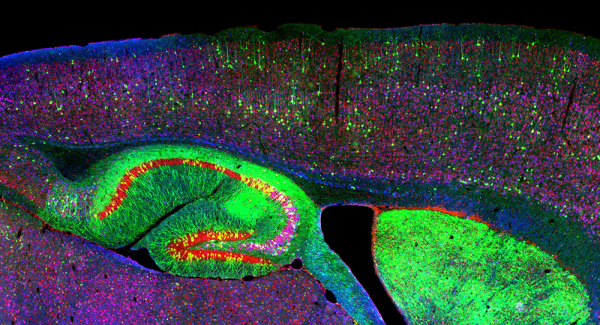

If a creative primary process can show itself only within the constraints of a monitoring secondary process, one must inquire into the nature of constraint. A nondialectical perspective treats constraint as either good (purpose) or bad (inhibition). Maslow (1968) saw social constraints, normative expectations, and peer pressure as barriers to creative expression. A person whose behavior is produced by habit and limited by fear cannot be creative. Professional expertise allows a person to master skills, technique, and ways of thinking (Fleck, 1935). Expertise provides the box within which people think and act efficiently. The dialectical perspective suggests that this box is necessary for out-of-the-box exploration and innovation. Gutenberg had mastered the technology of his time (Figures 1a and 1b).  He understood the engineering of the wine press and he knew about movable type. His creative contribution was to think neither as a vintner nor as a scribe. By combining the mechanics of the press with the combinatorial potential of letters, he revolutionized communication.

He understood the engineering of the wine press and he knew about movable type. His creative contribution was to think neither as a vintner nor as a scribe. By combining the mechanics of the press with the combinatorial potential of letters, he revolutionized communication.

Mednick (1962) proposed a cognitive theory of how ideas are mentally organized, and how this organization depends on the depth of expertise. In individuals with a steep associative hierarchy, knowledge is tightly packed. An engineer’s mental space is a dense cluster of concepts, where each concept readily activates other concepts within this space. Concepts outside of this professionally defined space are difficult to reach. Individuals with a flat associative hierarchy more easily access remote associates. This is a dialectical idea. Expertise is important, but too much of it is constraining. Mednick developed the famous “Remote Associates Test” to quantify the gradient of association. If, for example, the words ‘car,’ ‘cue,’ and ‘swimming’ are shown, a person with a flat associate hierarchy will be quicker to pinpoint the word ‘pool’ as the common (and thus remote) associate than a person with a steep (or no) hierarchy. Mednick’s thinking is Guilford’s in reverse. Guildford would ask respondents to list words that are related to the word ‘pool’ but not to one another.

Dialectic 4: Creative Destruction

Schumpeter (1942), the influential apologist of cyclical capitalism, asserted that economic downturns, even catastrophic contractions, are instances of creative destruction. The destruction of the old is necessary for the genesis of the new, and potentially better. Rank (1925), the influential Neo-Freudian, elevated the dialectic of destruction and creation to a “general life principle.” Rank would have had unlikely allies among the Gestalt psychologists. The key concept of the Gestalt theory of perception is Prägnanz, the idea that the mind interprets a bundle of stimuli in terms of the best-fitting configuration, thereby rejecting all alternatives. Perception is creative as it adds interpretation and coherence to disparate stimuli. As only one interpretation can rise to consciousness, all others must be destroyed subliminally. Likewise, creative design and creative action must try and discard all but one possibility. Rank asserted that the inverse is also true, that every destruction entails creation. This is a bold and probably false claim. It is safer to say that every destruction contains the seed of creation. Whether new creation comes to pass depends on the whole set of dialectics.

Dialectic 5: Disturbed Homeostasis

Any single-minded emphasis on the primary process makes creativity look easy and invites an illusion of wish-fulfillment. Who would not like to get something for nothing? Exploiting this illusion, self-help gurus may write books on 7 +/- easy ways to become more creative. A dialectical perspective on creativity respects the critical role of effort. Russell (1930) described how he would dedicate sustained mental effort to difficult intellectual tasks. If he failed to produce a solution after weeks or months of work, he would suspend his conscious efforts, expecting that mental work would continue in the psyche’s underground. Often, he found this attitude rewarded when after some time a solution would present itself seemingly out of nowhere. Russell understood the dialectic of effort and surrender, thus anticipating the psychology of the incubation effect (Ellwood, Pallier, Snyder, & Gallate, 2009). This dialectic is a general life principle on a par with Rank’s. It is easily understood with the analogy of the body. A healthy body requires a balance of exertion and rest, and so it is with the mind. It is not the homeostasis that is critical, but the return to homeostasis after a period of stress.

Dialectic 6: Out of Mind

Linear thinking and the quest for comfort stand in the way of appreciating the dialectics of creativity. Gurus and their admirers may take note of the finding that positive mood is associated with creative ideation (e.g., Guilfordian divergent thinking) and problem-solving (e.g., Dunckerian design). Research indeed supports a causal link. Davis (2009) found in a meta-analysis of relevant studies that the induction of a positive mood facilitates creativity. Interestingly, the principal mechanism at work is not the valence of the mood per se. Although it may be true that being happy makes one bolder and more confident and thereby creative, a simple associationist mechanism seems to be sufficient. Thankfully, most people have stored more positive than negative memories. The valence of the mood state then selectively makes memories of the same valence accessible. This ‘cognitive priming’ (Isen, 1999) regulates the amount of material available for consideration in a creative context. The dialectic is that humans have limited control over their mood states. Mood is a signaling system, honed by evolution, which tells a person how well or poorly things are going at the present time. If mood came fully under voluntary control, its adaptive function as a signaling system would be lost. Dialectically-minded individuals can, however, trick themselves into positive moods by exposing themselves to situations that make them feel good. A related dialectic is power. Interpersonally powerful individuals are less constrained by social fears or habits. Hence, they are more creative than less powerful individuals (Galinsky, Magee, Gruenfeld, Whitson, & Liljenquist, 2008). Yet, they can scarcely choose to be powerful in a direct way. Their minds must trick themselves into feeling powerful; for example, they can adopt an open, expansive body posture (Carney, Cuddy, & Yap, 2010), or they can brandish power tools such as jackhammers, drills, or industrial-strength vacuum cleaners.

Dialectic 7: Progress through Defense

A final dialectic lies at the fault line between creativity and psychopathology. Freud (1905) believed that cultural production (creativity) is due to the sublimation of inadmissible sexual impulses. Weber (1934) observed that Protestant Christians are raised on the notions of depravity and damnation. Those who subscribe to the doctrine of predestination are most likely to work hard and invest their gains in an attempt to decode a signal of God’s grace. In a creative line of experiments, Cohen and colleagues put Freud and Weber together, demonstrating that sexually perturbed Protestants produce more creative output (poems, clay sculptures) than do Catholics, Jews, or unperturbed Protestants (Kim, Zeppenfeld, & Cohen, 2013). Like the other dialectics, the dialectic of cultural progress through psychological defense offers no single linear route toward creativity. Creativity emerges from conflict and contradiction. This dialectic suggests that, much like the consequences of creativity need not be positive, so is there no reason for all sources of creativity to be socially desirable or rational.

Conclusion

The dialectical approach to creativity overcomes linear models. Although linear models may be useful approximations, they fail to capture the dynamic nature of creativity. It may be true and useful that taking a walk and letting the mind wander allows a creative flow of ideas. Experimental studies that support such notions are designed within the linear paradigm (Baird, Smallwood, Mrazek, Kam, Franklin, & Schooler, 2012), but the linear approach overlooks the necessity of opposing forces. Playfulness needs oversight (dialectic 1), chance needs direction (dialectic 2), innovation needs expertise (dialectic 3), creation needs destruction (dialectic 4), homeostasis needs stress (dialectic 5), mental ideation needs external stimulation (dialectic 6), and cultural progress needs psychic struggle (dialect 7). Regarding simple linear models as only partially correct (and thus categorically false), the dialectical perspective cautions against the idea that simple recipes for the enhancement of creativity are all we need to know. Seeking to raise creativity by assertion is about as promising as commanding a person to “be spontaneous!” Dialectically speaking, such efforts are not entirely futile; they just need to be understood within their dynamic context.

The dialectical perspective is similar to dual-process theories of cognition in that both assume a psychological polarity. Dual-process theories distinguish between efficient but imprecise processes (intuition, perception, emotion, heuristic thinking) and inefficient but precise processes (deliberative thinking). The two types of process or systems are assumed to work either in parallel or serially. According to the latter, more popular, view, the second type of process monitors what the first type of process is doing and occasionally steps in to correct errors. In contrast, the dialectical perspective assumes that interesting phenomena, such as creative thought, emerge from the tension between opposing psychological forces. Neither force is able to produce a result on its own.

Consider the Müller-Lyer illusion as an illustration (Müller-Lyer, 1889). According to dual-process psychology, perceptual processes yield the false impression that the two lines differ in length, while the cognitive processes know better – although they are unable to change the perception itself (Sloman, 1996). According to the dialectical perspective, one type of mental analysis determines that the two long vertical lines are identical in the way they stimulate the sensory apparatus. Another type of analysis notes that the short oblique lines suggest a special orientation. One vertical line appears to be the outer edge of a three-dimensional body, while the other appears to be the inner edge. The dialectical solution is to assume that the line appearing to be the inner edge is farther away, and that because it is identical in length according to the first analysis, it must in fact be longer. The illusion arises from the dialectic of a mismatch between physical stimulation and intelligent inference. Perception is creative.

Glossar